Most physicians are aware of the many medical advances developed by Army Medicine during wartime that are subsequently applied to patient care in the civilian realm. Contributions of Army Veterinary Medicine to civilian veterinary and human medicine is unfortunately often overlooked. This June marks the 99th year anniversary of the formal establishment of the U.S. Army Veterinary Corps by an Act of Congress on June 3, 1916. This watershed date brings to mind a piece of veterinary and medical history from the Vietnam War – a history that links an outbreak of canine disease in Southeast Asia to human disease in the United States. The story emphasizes the importance of collaboration between physicians and veterinarians.

USMC PFC Waldo Roame and his scout dog, Hobo, in action in 1968 during Operation Meade River, 13 miles southwest of Da Nang. More than 5,000 Marines participated in the cordon, the largest heli-based operation in Marine Corps history.

Photo Credit: USMC

Some History:

As in previous wars, US and Australian military forces used working dogs in a variety of capacities in the Vietnam conflict. These included scout, sentry, and tracker roles. At the end of 1968, 1,099 combat dogs were working for the US Army, Marines and Navy and the Australian armed forces in the Vietnam theater of operations. (Click here for a history of Vietnam War Dogs.)

Veterinarian, Capt. William T. Watson, on right, treating a scout dog, “Gunn,” wounded by shrapnel, at the 936th Vet Detachment War Dog Hospital, located at Tan Son Nhut Air Base. Nov 30, 1968

Photo Credit: Army Medicine.

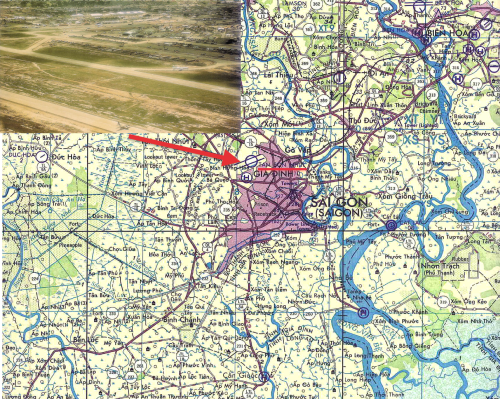

US Army Veterinary units provided care to these animals, as well as performed other public health tasks in South Vietnam. In 1968, approximately 50 veterinarians were serving in South Vietnam across four tactical zones. (See map and table below. Click on the image for a larger version.)

An Outbreak Begins:

In September, 1968, veterinary units started treating dogs with epistaxis (bleeding from the nose). Epistaxis is profoundly unusual in dogs. And these dogs had severe outcomes. The first death was a sentry dog from the 212th Military Police Company stationed at Long Binh. As more cases occurred, it was recognized that nasal bleeding could be unilateral or bilateral. Affected dogs had vomiting with dehydration, weight loss, lethargy, lameness, and cutaneous bleeding (ecchymoses and petechiae). Clinical workup was notable for leukopenia (low white blood cell count) and progressive anemia. The disease inexorably led to death.

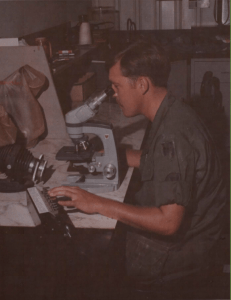

SP4 Francis Heyniger, lab technician, performing a WBC differential on a war dog at the 9th Med Lab, Long Binh, Vietnam.

Photo Credit: Army Medicine

The first cases of the disease were reported from units based at Long Binh, Chu Lai, Tan Son Nhut Air Base, and the area around Pleiku. By July 1, 1969, 160 fatal cases had been reported in 20 of the 22 US Army infantry scout dog platoons, all of the military police dog units, as well as some US Air Force and Marine dog units. Cases were reported from units throughout South Vietnam.

Epidemiologic observation led to the conclusion that the disease was being transmitted from dog to dog. All the sick animals had been kenneled together at two bases (Long Binh or Saigon) or had been exposed to sick dogs that had previously been at the two bases.

Tan Son Nhut Air Base was located Northwest of Saigon, South Vietnam. Inset, photograph of the air base in June, 1968.

Photo: Common Domain.

After September, 1968, all military dogs with epistaxis were referred to the 936th Medical Detachment at Tan Son Nhut Air Base located in southern Vietnam, Northwest of Saigon. (See Map and Photo Inset.) This was an attempt to avoid transmission of the disease from ill to healthy dogs. Because the etiology was unknown and the dogs died of hemorrhagic (bleeding) manifestations, the disease was initially named idiopathic hemorrhagic syndrome.

A thorough review of identified cases of the disease was conducted in January, 1969. Based on signs and symptoms, focus was on an unknown infectious cause. The “differential diagnosis,” the list of possible causes of the disease, included a diverse group of pathogens.

Routine blood cultures, which are used to identify bacterial pathogens, were negative, eliminating typical bacteria as a cause. The diagnostic focus turned to rickettsial, viral and hemoprotozoan pathogens.

Affected dogs were more likely to have been housed in kennels with heavy tick infestations. Researchers focused on a possible tick-borne pathogen. The Army veterinarians collaborated with researchers at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. They drew blood from affected military dogs and inoculated test animals. These transmission studies showed disease could be transmitted by blood to beagles. On peripheral blood smears, Babesia was identified in the beagles.

Babesia: A tick-borne Protozoan Pathogen:

Babesia is a hemoprotozoan pathogen, similar to Plasmodium (which causes malaria) – both infect red blood cells causing anemia. However, Babesia is tick-borne and malaria is mosquito-borne. Multiple Babesia species infect a variety of mammal species. B microti, for example, is one species that infects humans and may cause disease, usually in immunocompromised or asplenic individuals, called babesiosis. Unfortunately, early experimental results suggesting Babesia infection were not consistently reproducible, nor was Babesia consistently found in affected dogs in Vietnam. This outbreak was not due to Babesia.

With further review, it was noted that an identical disease had broken out among French military dogs in Tunisia and, more recently, in 1963 among British military dogs working in Singapore. Furthermore, the US military had purchased Labrador retrievers from the British Army and imported them from Singapore to Vietnam in late 1966 and early 1967. Perhaps these dogs were a source of disease? The British had termed the disease tropical canine pancytopenia, so given they had first naming rights, further work on the disease was pursued under this moniker.

DL Huxsoll speculated the disease was due to Ehrlichia in 1969. By mid-1970, he and his colleagues at Walter Reed confirmed tropical canine pancytopenia was due to canine Ehrlichiosis, related to infection by Ehrlichia canis. Ehrlichia are intracytoplasmic bacterial pathogens, in other words, they live inside the cytoplasm of host cells. In this case, the organism lives inside the very white blood cells that would normally fight off infection. Ehrlichia can not be identified by routine blood culture, though clusters of the infecting bacteria can be visualized microscopically on peripheral blood smears. You have to know to look for these inclusions, though, otherwise they are easy to overlook. In the case of tropical canine pancytopenia, researchers found intracytoplasmic inclusions (called morulae) on peripheral blood smears of affected dogs. In this particular case, clusters of bacterial cells were seen in monocytes, characteristic of Ehrlichia canis. Dogs that were experimentally inoculated were also universally found to have Ehrlichia inclusions.

Tropical Canine Pancytopenia, AKA Canine Ehrlichiosis:

Canine ehrlichiosis had been recognized in Africa starting in the 1930s. In 1957, the infection was described in the New World for the first time, in the Netherland Antilles. And it was first described in the United States in 1962 when it was reported from Oklahoma. Walker, et al 1970, noted in a prescient comment regarding the Vietnam outbreak, “with modern air travel and international movement of pets, tropical canine pancytopenia might be a diagnostic problem outside of tropical and semitropical areas.”

In actuality, the organism was already there. Dr. Sydney Ewing received his PhD from Oklahoma State University based on his work studying canine Ehrlichiosis in Oklahoma. So the disease the British named tropical canine pancytopenia was not only tropical, it was the previously known disease, canine ehrlichiosis. Based on Ewing’s work on ehrlichiosis, treatment with the antibiotic tetracycline was tried in Vietnam. Tetracycline was not only used both to treat ill dogs, but also to treat apparently well dogs in a prophylactic effort to prevent disease. The epizootic slowed after institution of these measures.

The brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus) is the vector of canine Ehrlichiosis. This tick was found in the kennels in Vietnam, and it is the most common tick found on dogs in the US as well. A cosmopolitan species, it is found pan-globally. As an aside I should note, that this tick only rarely bites humans.

Rhipicephalus sanguineus (the brown dog tick)

Creative Commons License:

Dantas-Torres, F. 2010. Biology and ecology of the brown dog tick,Rhipicephalus sanguineus. Parasites & Vectors 3:26

Veterinary researchers were on the forefront of discovering Ehrlichia and the pathogen’s epizootiology, describing the clinical manifestations of disease, and determining most effective treatment regimens. Researchers developed cell culture systems and “clean” tick colonies that were crucial to study of the infection.

Ultimately, it is estimated that some 200- 250 military dogs in Vietnam died from tropical canine pancytopenia. Impact of the disease was greater than just the number of canine casualties, however. Operational efficiency of canine units was significantly impacted by ill dogs that recovered. At the end of the war when military units were withdrawn from South Vietnam, there was great concern that re-patriating military dogs would spread the disease to the United States. Partly because of this concern, the majority of war dogs were left behind in Vietnam.

The Canine-Human Connection:

This would be an interesting veterinary mystery if the story stopped there, but in 1987, infection with E canis was described for the first time in a human. The infection was zoonotic, i.e. the infection occurred in animals as well as humans. Ehrlichia were not known to infect humans, other than a rare illness caused by Neorickettsia sennetsu (formerly E sennetsu) in Japan and Malaysia.

But there’s more: in 1991, human infection with another Ehrlichia species was described by BE Anderson and colleagues in a US Army recruit stationed at Fort Chafee, Arkansas. Named Ehrlichia chaffeensis after the US Army installation, the species is related to E canis and, similar to that pathogen, infects monocytes. Infection with E chafeensis causes an illness in humans similar to Rocky Mountain spotted fever, with fever and rash. The organism also infects dogs and goats. In contrast to the tick vector of E canis, E chaffeensis is transmitted by the bite of the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum. The disease was named human monocytic ehrlichiosis.

Female adult Amblyomma americanum tick.

Common name: Lone star tick.

Photo Credit: Public Health Image Library, CDC

In the early 1990s, Johan Bakken and colleagues described a similar illness in humans in Minnesota and Wisconsin, far from the epicenter of human monocytic Ehrlichiosis in the central United States. The morulae, those intracytoplasmic inclusions, were found in granulocytes rather than monocytes. Symptoms of this new illness are somewhat similar to human monocytic ehrlichiosis, though without a rash. And yet another tick – the deer tick (Ixodes scapularis) – is the vector.

Female adult Ixodes scapularis tick.

Common name: Deer tick or black-legged tick.

Photo Credit: Public Health Image Library, CDC

Originally named Ehrlichia phagocytophila, this bacterial species has been moved based on molecular studies into another, closely related genus, and is now named Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Aside from identifying Ehrlichia canis in Oklahoma, Sydney Ewing also described another species, Ehrlichia ewingii, that infects dogs. In 1999, Buller et al described E ewingii infection in humans, so it too is zoonotic. A flurry of new diseases in humans and animals have been recognized in the wake of the outbreak of tropical canine pancytopenia in military dogs in Vietnam.

In Conclusion:

For decades, from the time Ehrlichia was first identified in Tunisia, the species existed in relative obscurity in the veterinary literature. As a result of a major outbreak of canine ehrlichiosis in Vietnam, US military and research veterinarians focused their attention on Ehrlichia. Directly because of the outbreak in Vietnam, the groundwork was laid for human medicine to recognize this fascinating group of vector-borne infections in people beginning in the 1980s. As tick-borne pathogens, Ehrlichia and Anaplasma infections are second only to Lyme disease in the number of people sickened annually. Earlier work of veterinarians paved the way to our understanding of these infections in humans. This is another parable of One Health, the integrative concept that the health of humans, animals, and the environment are connected.

(Click on table for a larger version.)

Acknowledgements:

I want to specifically acknowledge Dr. Sydney Ewing who first told me the remarkable story of canine pancytopenia in the late 1990s. His research has been crucial to our understanding of these diseases and I suspect I would not have ever heard the story of military war dogs and ehrlichiosis if it were not for meeting him.

The military history of tropical canine pancytopenia in Vietnam can be found in Dr. William Kelch’s master’s thesis cited below. His paper provided the military history of the epizootic, which is otherwise not found in the medical-veterinary literature.

References:

Anderson, BE, et al. 1991. Ehrlichia chaffeensis, a new species associated with human ehrlichiosis. J Clin Microbiol 29: 2838- 42.

Bakken, JS. 1998. The discovery of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J Lab Clin Med 132(3): 175- 80.

Buller, RS, et al. 1999. Ehrlichia ewingii, a newly recognized agent of human ehrlichiosis. N Engl J Med 341: 148- 55.

Chen, S, et al. 1994. Identification of a granulocytotropic Ehrlichia species as the etiologic agent of human disease. J Clin Microbiol 32(3): 589- 95.

Donatien, A & F Lestoquard. 1935. Existence en Algerie d’une Rickettsia du chien. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 28: 418- 19.

Dumler, JS, et al. 2005. Human granulocytic anaplasmosis and Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Emerg Infect Dis 11(12): 1828- 34

Ewing, SA, et al. 1971. A new strain of Ehrlichia canis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 159: 1771- 4.

Huxsoll, DL, et al. 1969. Ehrlichia canis- The cause of a haemorrhagic disease of dogs? Veterinary Record 85: 587.

Kelch, WJ. 1977. Military working dogs and canine Ehrlichiosis (tropical canine pancytopenia) in the Vietnam War. Fort Leavenworth, KS. (Available here.)

Maeda, KE, et al. 1987. Human infection with Ehrlichia canis, a leukocytic Ehrlichia. N Engl J Med 316: 853- 6.

Nims, RM, et al. 1971. Epizootiology of tropical canine pancytopenia in Southeast Asia. J Am Vet Med Assoc 158: 53- 63.

Smith, RD, et al. 1976. Development of Ehrlichia canis, causative agent of canine ehrlichiosis, in the tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus and its differentiation from a symbiotic richettsia. American Journal of Veterinary Research. 37: 119-126.

Walker, JS, et al. 1970. Clinical and clinicopathologic findings in tropical canine pancytopenia. J Am Vet Med Assoc 157: 43- 55.

Really liked this post Dr. Sellman! Interesting history and it makes it easier to remember this group of pathogens together and some of their key features.

LikeLike